Part One: Vira and Ada

1.1 Sary, Poltava region, Ukraine, 1991

Paper dashes

My great-grandmother Vira was a primary school teacher. She worked her entire life at the same school in a village in the Poltava region, where she taught children how to read and write.

At the beginning of the school year, in their first ever class, she gave the children a sheet of paper and asked them to do with it what they could: those who knew how could write some words or letters, and the others could draw something. One little boy could not do anything, so he drew a simple vertical dash. When he had to turn in his little sheet of paper, he burst into tears. Afterwards, of course, he learned everything he needed, and that dash had no influence over the rest of his life. My great-grandmother told me this story when it was my turn to learn to write, when I was having trouble and she tried to cheer me up.

She was a daughter of an enemy of the people. Her father, Erast, was a village bookkeeper who was executed in 1938 for his ‘terrorist activities’. By then, he was already an old man, with nothing but his job, his farmstead, and his sick wife. My great-grandmother did not have a husband, but this did not make her life more difficult. Being the daughter of an enemy of the people is what made things difficult.

My other relatives from back home, the lucky ones who were not executed, worked on the kolkhoz, a state-owned farm where people worked in return for trudodens. For every trudoden, or day worked, a dash would be marked down in a special record book. This was their payment instead of money. A system made by men in power who were paid in many things more than dashes.

1.2 Sary, Poltava region, Ukraine, 1992

Leeches

One summer in the village, we kept goslings, many lovely, plump white goslings. When the goslings had grown a little bigger, they started waddling to the small man-made pond outside the village to swim and to do the things goslings do when they are not locked up in an uninteresting backyard.

My job was to accompany the goslings to the pond every morning and coax them back home with me. Sometimes they came willingly, and sometimes they just honked lazily from the other side of the pond, where they had already settled down for the night, and ignored my desperate shouts and attempts to persuade them that they would all, silly birds, get eaten by the foxes. Then my grandmother Ada would come and tell them to go home, and they obeyed straight away. They always listened to her.

In the pond there were leeches, many hungry leeches that wriggled to latch onto some pretty, silly little gosling. More often than not, they clamped onto a foot, but the most shameless could burrow into the corners of the gosling’s eyes. I knew that all you had to do to get rid of leeches was to sprinkle salt onto them, but what could you do if they were in an eye? My grandmother knew. Back then, I believed that she said, ‘Get off them!’ in a strict voice, and they would fall off straight away. With her, everyone always did what they were told straight away.

1.3 Margilan, Uzbekistan, 1941

Long roads

When the Third Reich attacked the Soviet Union, and the Germans were near on the approach, my great-grandmother Vira made a decision. The only treasure that she had was her nine-year-old daughter, Ada. How could a woman protect herself during war? What’s more, a woman and a child? What’s more, the daughter of an enemy of the people with a child?

Vira packed a suitcase, took Ada, and joined the evacuation. Long roads and unending weeks of packed trains took them to Uzbekistan, to a town called Margilan.

Fifty years later, when they both told me this story, Vira explained this choice of place like so:

‘We didn’t know anyone or anything, not anywhere. We didn’t know where to go or what to do. We heard the name of this town and we liked it. A place with a beautiful name can’t be a bad one.’

Seventy years later, when both of them were long gone and there was no one left to ask, every time I tried to recall the name of the town that had sheltered two women I loved from the war, I would recall it in the following way: the name of the town begins with M, and it was very beautiful. That was how I remembered it each time.

As an adult, I might be so organised as to print out a map and draw a thick green highlight around Margilan.

1.4 Margilan, Uzbekistan, 1942

Cotton hair braids

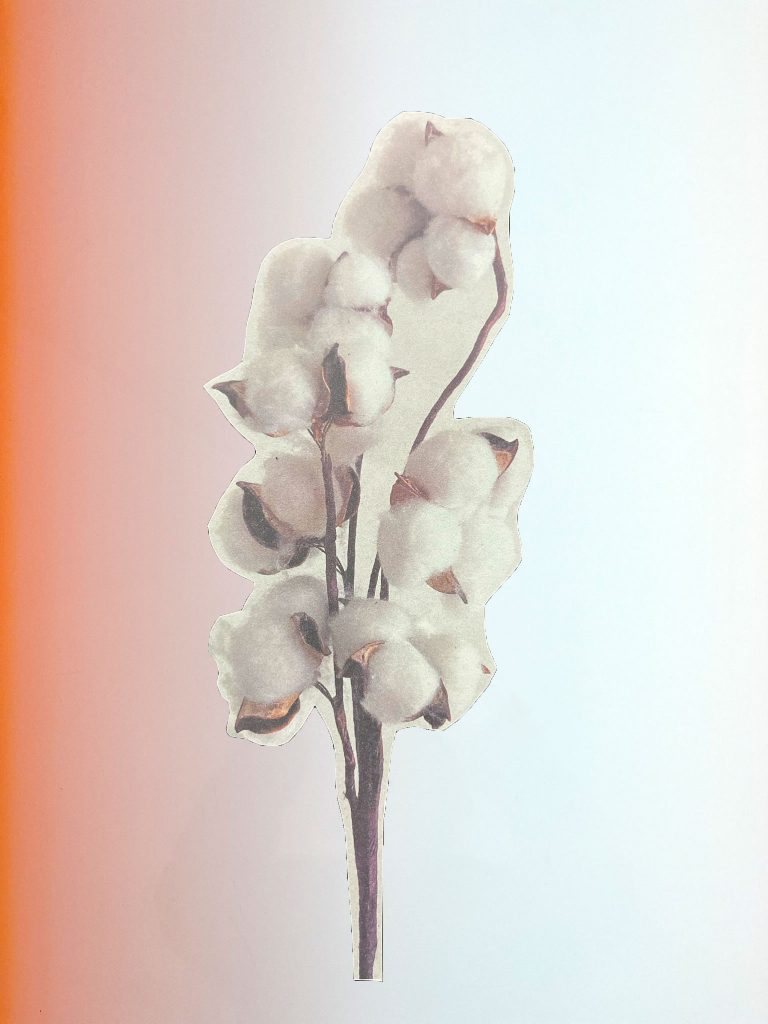

‘In Uzbekistan, women kept very, very long hair that was always worn in braids, with many small twists,’ Vira told me, as she combed out my thin hair with a thick comb.

We were in the village, and I had once again come home with lice.

‘When the women in Uzbekistan washed their hair,’ Ada told me while she soaped up my head with that unbearably stinky shampoo (which was fatally stinky for the lice), ‘they would plait cotton flowers in each of their braids. When they walked down the street, the white flowers in their black braids bobbed up and down at each step.

In Margilan, my great-grandmother worked as a teaching assistant in an orphanage, which provided her and her daughter a place to sleep, and when the season started, she would pick cotton on the farms. Both of them were starving. Neighbour women helped them survive. Neither of them would tell me about this.

When no one was looking, I would make a thin little braid and try to shove a dandelion in it. The dandelion would not stay in. After lengthy trials and tribulations, I would eventually give up and plait some little daisies into my pigtails that were as thin and limp as mice tails.

1.5 Margilan, Uzbekistan, 1942

Malaria melons

‘We had to be very careful with the melons during the evacuation,’ Vira told me. At this, Ada chimed in: ‘If you ate the wrong melon, it could give you malaria. We had to drink this horribly bitter cinchona for the malaria. I never wanted to take those bitter tablets. Though I’ll tell you a secret I learned back then: if you peel off a thin, see-through bit of skin from an onion bulb and wrap the pill inside it, then you can’t taste it at all! Try it.’

I was sick, short-tempered, I didn’t want to swallow any onion pills and I didn’t want to eat any melon. Their stories from the evacuation unfurled before my fever-bound eyes like my own pocket theatre: extravagant scenes from wartime where I could not separate truth from fiction, separate the stories that really happened from the stories that just so happened to suit my tempermental mood.

My grandmother brought three photographs back from Margilan: one of Ada doing the splits, side-on, her little arms straining to make a circle; Ada and some other children in a difficult gymnastic pose; Vira and the other assistants at the orphanage. Who were those other children? When I was a child, I often peered into their faces, but I never asked the question. These photographs, like many others and like much else, disappeared during the other occupation, which, unlike the swiftly-passing German one, is still in place in my city, Donetsk.

1.6 Sary, Poltava region, Ukraine, 1944

Long dresses

The moment the news of our village’s liberation appeared in the newspapers, Vira started getting ready for the journey home. They travelled a long time because they had no money for the tickets, and the road led fearfully far away.

In Sary, they were met with the ruins of their previous life and an uncertain future. Vira once again set herself up as a teacher in the same school. They had a sewing machine and Ada learned how to sew clothes. She sewed clothes — or rather patched them together from old ones — for her friends, peers and for the children in her neighbourhood.

The basic principle of fashion design back then, as my grandfather told me, was extraordinarily simple: girls’ dresses had to be sewn as long as possible, so even if a girl was a fast grower she could still keep wearing it. Of course, boys’ trousers were also made for growing.

Varia, the sister of my (at the time, future) grandfather, did not bother herself with the extra length and showed off her short new dress to her friends.

1.7 Sary, Poltava region, Ukraine, 1995

A bottle full of cockroaches

In our village there were countless ways of putting a curse on someone. Many things foretold immediate death, destitution, and continuous misfortune. In the ability to traverse between barely noticeable signs of fatal danger lay, as it seemed to my childhood self, the life and health of all my nearest and dearest.

My grandmothers enjoyed a considerable degree of respect in our village, since Vira was a teacher who worked her whole life in the local school, and Ada was the teacher’s daughter who made it out of the village and became headmistress of a school in town. Nevertheless, they still provoked a considerable degree of envy. This envy never expressed itself openly, but from time to time would reveal itself in the form of a comb left near their house, a needle stuck in their gate, obscure chalk markings, or in a handkerchief or wad of hair tossed onto the ground near their house. Once they found a strange, narrow, thin old bottle that had been half-buried in our garden, and when it was dug up, they found it full of scurrying, live cockroaches.

But I knew that this was nothing to worry about, since all one had to say was: Your charm becomes your harm, your word becomes your hurt, your spell becomes your hell. And all those curses would go back to the person who made them.

Ada died early, and I never managed to thank her for countless things. Curses had nothing to do with her death; it was just a thing that happened. The things in life that last are never the ones you would want to.

1.8 Donetsk, Ukraine, 1998

The Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopaedia

On our bookcase in Donetsk there were twelve volumes of the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopaedia, a long row of dark-green spines. The volumes’ strange titles with words I had never seen before reminded me of train schedules to mysterious, faraway places:

Avocet — Cerebellum

Gyttja — Lavoisier

Perigee — Swedenborg

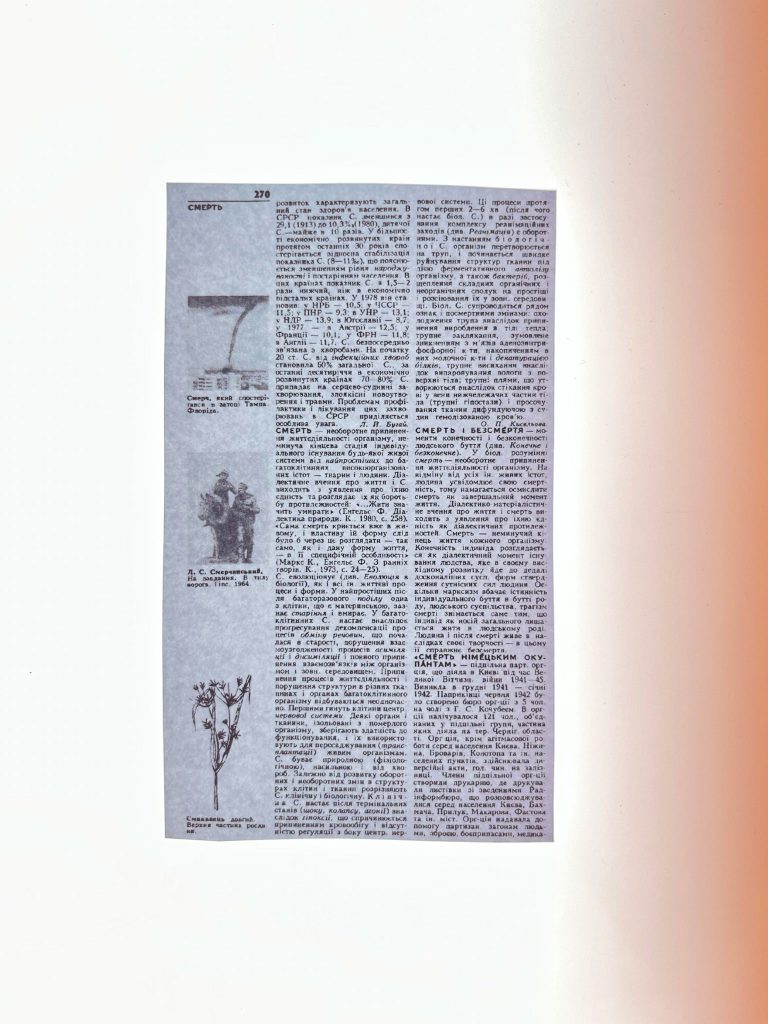

I was often perplexed by the order and the titles of the articles inside. For instance:

‘Death’

‘Death to the German occupiers’

‘Death and immortality’

‘Debearding’

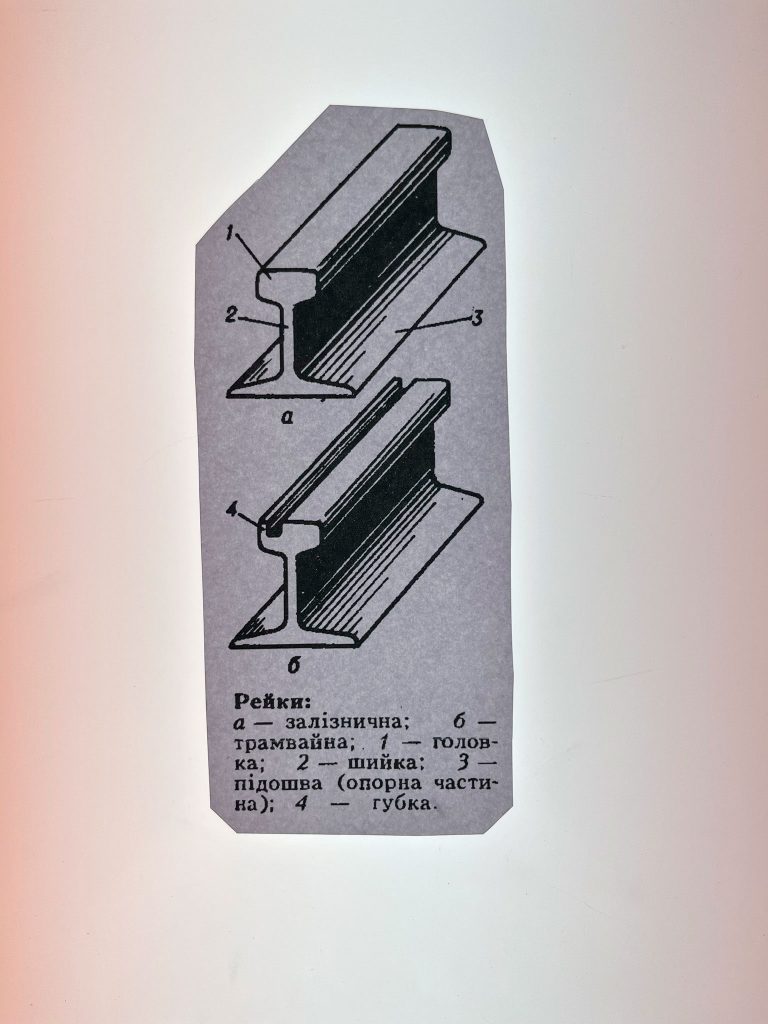

The illustrations that ran vertically alongside the elongated columns of text in miniscule type were not much better. Next to a pseudoscorpion that looked like a scorpion was an illustration of a pseudosphere that did not resemble a sphere at all. The juxtaposition of such unrelated things that pretended to be something they were not infuriated me.

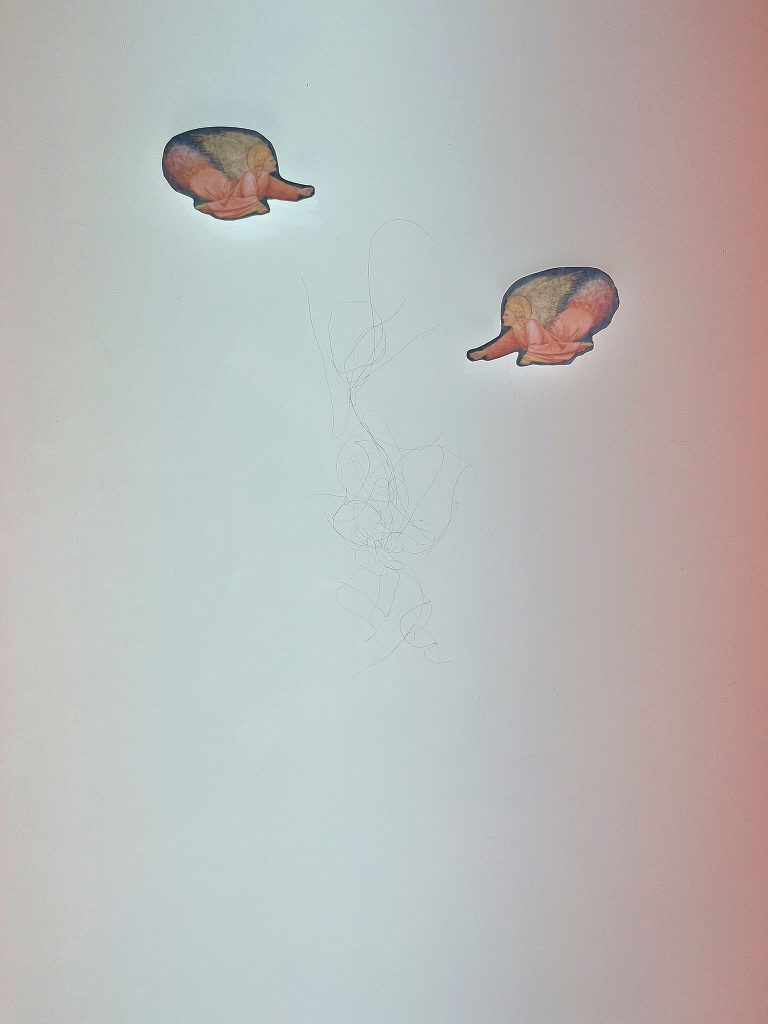

There were other, huge colour illustrations that I adored and could pore over for hours: a dissected human body, the bones surrounded by a grey contour of skin; next to it, a dissected bird; above their dissected heads glowed the bones of some dinosaur; two dissected tractors portraying the overall structure of tracked and wheeled tractors; multicoloured birds’ eggs on a black background that looked like planets in dark space; traditional pysanky Easter eggs decorated with ecstatic designs of flowers, fish, and birds; six different coloured mice gathered in a circle, as if at a board meeting; illustrations of clouds; a drawing of the autonomic nervous system that resembled a string of balloons.

My grandfather and grandmother collected the volumes of the encyclopaedia over time, exchanging it for bundles of old newspapers at the paper recycling centre. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and my grandmother’s passing shortly after, my grandfather, who sincerely hated everything that was Soviet, handed these twelves volumes back to the paper recycling centre.

It was only as an adult that I found out that this encyclopaedia had been edited by the writer, poet, and political figure Mykola Bazhan, who, as much as possible, tried to cram any snippets of information about Ukrainian culture in-between the propaganda.

1.9 Donetsk, Ukraine, 2001

Long hair

My great-grandmother’s hair, which had never been very pretty, became as thin and see-through in her old age as a spiderweb, and she shrank until she was hunched over and tiny. She sharply refused to cut her hair.

‘You see,’ said Vira, ‘when I die, the angels will fly to me and pull me out of hell by my hair. But if I cut my hair there’d be no plait to grab me by. What would I do then? I’d have to stay in hell.’

What surprised me most in this story was how my great-grandmother, who had devoted her whole life to other people’s children and who was visited by old – now in all senses of the word – students, including the boy with the dash, right up until her death, could end up in hell.

I never found out whether she believed in God or not, whether she truly believed in heaven and hell, or whether she was joking when she talked about those angels. One thing I did find out is that I have the same thin hair as hers: thin and weak. I cut my hair quite short, so when my turn comes, I will have no chance of ending up in heaven and I will be stuck in hell.

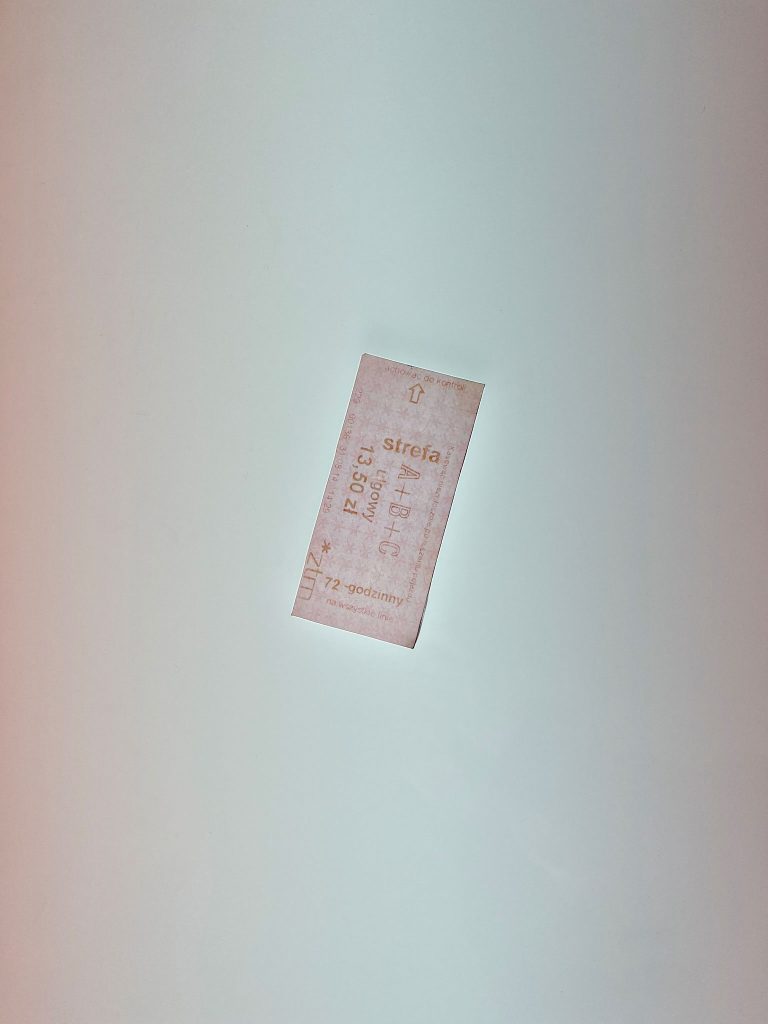

1.10 Poznań, Poland, 2019

A paper tram ticket

I shove myself onto the tram at the end of the line, along with a chattering crowd of students, who, like myself, are returning home after a full day of lectures. I look at their faces and see many foreign students clearly on their Erasmus year. It was the start of the new semester. One boy asks me in English how to buy a paper ticket. There’s no way, kid. You’re in an urban paradise now, I think. No one uses paper tickets here, let alone pays for them in cash. We chat a little, and I show him how to buy a ticket on the app. He gets mixed up and says a word in Russian, so I ask him where he’s from and whether he speaks Russian. He is from Uzbekistan and switches to Russian with me, seeming to find it easier than English.

Without thinking too much about it, I ask him about Margilan. He comes from the Ferghana Valley and of course, he says, he knows Margilan well. Why am I asking? I find myself telling my family story to a stranger who merely wanted to buy a tram ticket. He listens with concern, glad that my grandmothers found refuge in his country. ‘By the way,’ he asks, ‘how’d you know I spoke Russian? I don’t like Russian at all. I don’t like Russians either. Everywhere they go, they act like they own the place. It’s different with your grandmothers because there was a war and they went back straight after.’

I begin to feel ashamed.

He gets off before me, and I sit and think about how when I met a stranger on a Polish tram the common theme between me and him was colonial wars and colonial trauma.

Part Two: Shura

2.1 Donetsk, Ukraine, 1960s

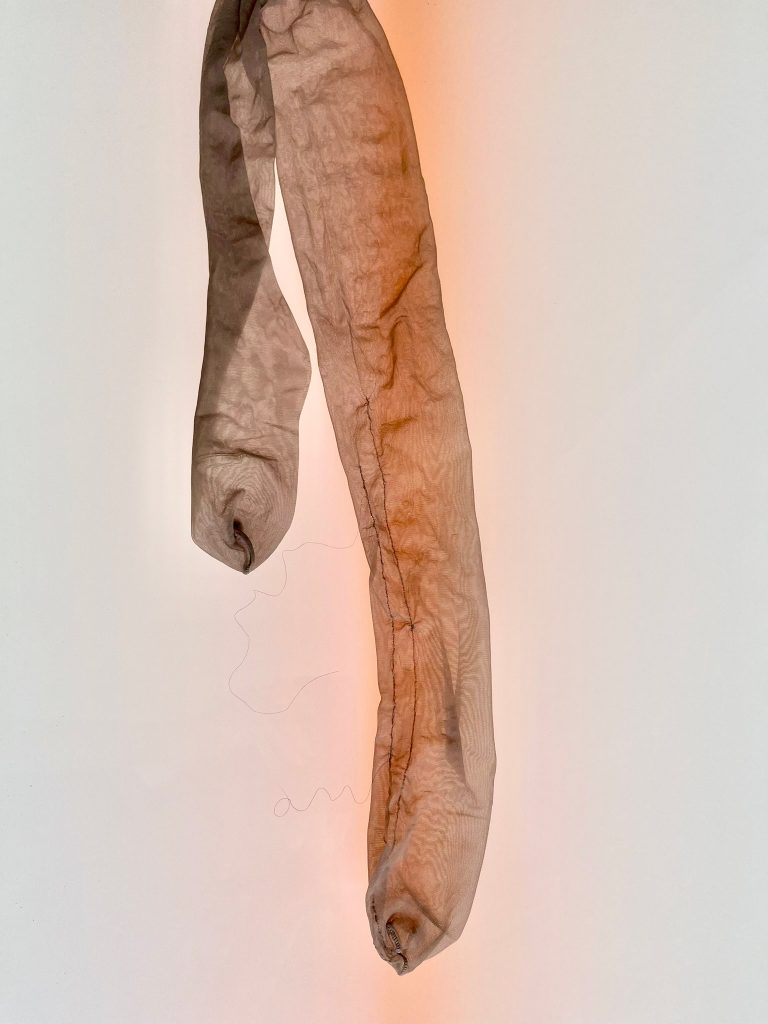

Hair-darned stockings

My grandmother Shura used to darn her stockings with her own hair. This made the seam so thin that one could barely tell that there was once a hole. I never saw her do it, but this was because I only knew her when she was already an old lady and her incredible hair had long become a part of family lore, just like the legends of the stockings.

Shura not only sewed with hair but did a wonderful job with thread. She was a professional women’s fashion designer who could design and sew anything for anyone. She was, it was said, a careerist, working at the Ministry for Light Industry, andpeople at work claimed she was a tricky character. At home, however, you could not find a gentler person.

Her relationship with reality was distinctive: she could raise or lower her body temperature and change the composition of her blood at will. No one had a clue how she did this. Magical realism was not very welcome in the USSR, which is why the Soviet psychiatric system later took an interest in her. Fortunately, even a directoress of a psychiatric department would need nice new dresses from time to time, so she stayed free.

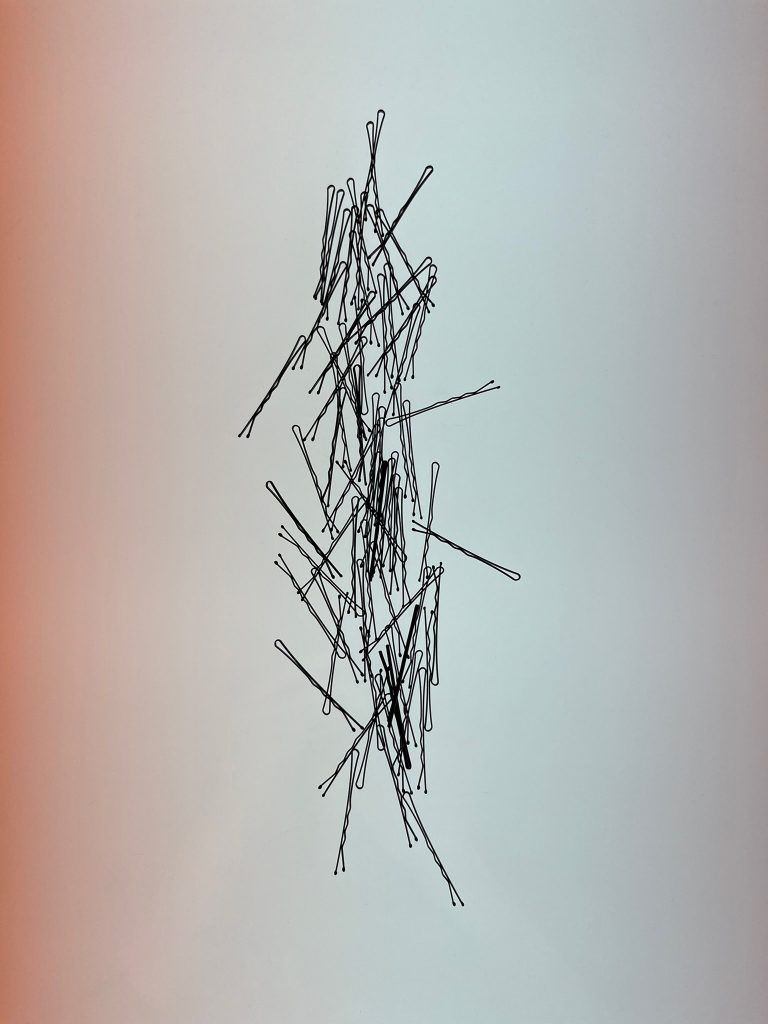

2.2 Donetsk, Ukraine, 1970s

Hairpins

Shura’s hair was so long and strong that she was forced to cut it off, as the weight of it and all the pins she stuck into it gave her a permanent headache.

I think of her, a beautiful, able woman in an unwelcoming mining town, who would comb out her long hair, twist it into a complex hairstyle, painstakingly pin it with dozens of hairpins, and rush off to work, where her subordinates were a little afraid of her; where she would sit at her desk, carrying all the weight of all that hair and the pins in it and all the weight of her tasks and responsibilities. How could that head not start to ache?

She had two children and a husband, a miner. She buried him when I was still a young child.

She rarely let her fantastic hair down, only in summer, when she would go to the seaside. She would walk along the sand down to the water, followed by animated shouts across the whole beach: Oh look, it’s a mermaid!

2.3 Donetsk, Ukraine, 1942

Big boots

‘When we worked for the German man, I milled grain,’ my grandmother told me. ‘I was fifteen. I had big boots, men’s boots, and I would pour a bit of grain into these boots and take it back home with me.’

I recorded her stories about the war on a cassette dictaphone and later painstakingly transcribed everything she said into a notepad. It was my homework. On yet another Remembrance Day for the Second World War, our teacher, who was not a history teacher but our Russian literature teacher (why did we study Russia’s literature at all?), gave us the task of recording our older relatives’ memories about the war.

Only Shura could tell me about the war in Donetsk. Her family did not try to evacuate — where could you go with children and livestock? — so her personal memories contained some nicely pre-prepared homework for me.

That was the first time she spoke to me about her experience of the occupation in the Donetsk region and about the famine. She had never mentioned either before. A deep boundary between the children’s stories and adult memories had been furrowed in her mind, and I did not dare ask her to cross this boundary.

2.4 Donetsk, Ukraine, 1996

Big brows

My grandmother also spoke about her father, who fought in the war.

My great-grandfather also fought during the whole of the war, and reached Kenningsburg, I wrote, in Russian, for my essay.

I wrote the former name of Kaliningrad, ‘Königsberg’, with so many mistakes that the teacher did not recognise it to even correct it. I barely mentioned my grandmother in the essay; she did not fight, after all.

Back then, war seemed like such a frightfully tough and important matter that only men did, going far away and doing something heroic in far away lands, protecting people from some other people in places whose names I could not pronounce.

I was twelve years old at the time and still had not the slightest clue that I would later end up working with historical memory and oral history.

I barely remember my great-grandfather; only his big, shaggy eyebrows and how angry he would get when I climbed on top of the table as a child. My brows are exactly the same as his. I still love to sit on the table, but now no one tells me off for it.

2.5 Donetsk, Ukraine, late 1990s

Three-metre tomatoes

When she retired, my grandmother settled in her father’s house. The town she lived in was officially known as the mining settlement of Lidiivka, but it was considered a part of Donetsk proper, and the city bus service had a stop there. To get to her house from the bus stop, you had to walk past the mine, where black puddles gathered after rain, and in winter the puddles were surrounded by an uneven circle of dirty white snow.

My grandmother tended a vegetable plot; the nearby mine didn’t bother her. As soon as she took to growing vegetables, the array of varieties and subspecies that appeared in her garden was so glorious that all her neighbours would come by to see them. She grew Jerusalem artichokes and these small, furry cherries that were supposed to be eaten whole; giant tomato plants that grew so big they had to be tied back higher and higher up their stems so they would not collapse. They climbed into the sky like crazy, as if planning to touch it. The tomatoes they produced were enormous, the size of my teenage head.

The tomato plants grew taller than my grandmother, which meant she had to stand on a chair to reach them, but soon this wasn’t enough. I waited for the time when she would have to climb on a ladder to reach her tomatoes.

How do you tie back a tomato stem that is bigger than yourself? Somehow my grandmother managed.

2.6 Donetsk, Ukraine, 2000

Six-metre bead necklaces

That year I acquired a Radiohead tape, a pirate copy. During the school summer vacation, my main activities were being bored, wandering around the quiet, warm neighbourhood of Lidiivka, and listening to my tapes. Out of a lack of something to do I learned how to smoke – back then everyone could get hold of fags, as the 18+ restriction only appeared when I myself was already 18+. I wore a vyshyvanka, an embroidered shirt, that my godmother had given me as a gift, and a six-metre-long bead necklace. Nice shirt, passersby would say to me, in Russian.

One time, wearing that getup – vyshyvanka, beads, and old jeans – I was kicked out of a church after I popped in, not in search of God so much as in search of some inner peace. For the Godly-dressed mean lady who kicked me out, the problem wasn’t my trousers or the lack of appropriate attire, but that through what was, according to her, a thin blouse I was godlessly showing off my foolish teenage flesh. When I got home, I added a few more metres of beads to my strings of necklaces. I have stopped looking for peace in churches.

As for Shura, when she realised that she was in need of God, she approached the question of faith as thoroughly as the Grand Prince Volodymyr of Kyiv when he was preparing to baptise Kyivan Rus: she buried herself in every possible religious tract and brochure, from the Koran to the holy texts of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, from the Bible to the most utterly minor sectarian works, and she studied it all diligently.

Like Grand Prince Volodymyr, she landed on the Christian faith – Orthodox, in her case.

2.7 Donetsk, Ukraine, 2001

November leaf fall

On my tape player, I would play tapes with tracks written by my friends. Back then we all wrote poetry to varying degrees of hopelessness and talentlessness, but full of a sincere teenage radicalism and a thirst for something new. None of us knew what this new something could be.

We had many ideas. We went to anarchist meetings, to poetry readings at the university literature studies department, underground concerts on building sites; we swam drunk in the quarries, drank coffee with our lesbian friends from the same literature studies department; others of us went to church. We drank vodka on an empty stomach, smoked Gitanes and Gauloises that you could only buy from one trusted woman at the market hall; we listened to Okean Elzy and read plenty of books from abroad (in translation), imagining ourselves as having lost our way from life’s beaten track like the beautiful and unhappy love-struck heroes of the novels we read.

Later, of course, we all grew up. Some of my friends from that time – those who survived – helped the Russians build the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic. But before all that, we would sit together on the grass in a circle, they would play their songs, and we would take turns reading poetry.

I would read Vasyl Stus:

A longing snap in an empty forest

And a piercing bird call.

Leaf fall.

Where could the butterfly alight?

2.8 Poznań, Poland, 17.07.2014

Sky lines

That day was my thirtieth birthday, and my family finally decided to leave Donetsk, by then already occupied by Russian militants.

After work, I turned on my phone and called my mother to ask how they were.

‘The plane,’ was the first thing she said. Then: ‘We got out ok. Have you seen the plane?’

For some time I could not gather what she was talking about, knowing they had taken one of the last trains out.

While still on the phone, I opened Facebook with my free hand to reply to birthday messages. My whole feed was covered in news about flight MH17, shot down by Russian terrorists.

297 dead.

Later, I was joined by some of my friends, more out of fidelity than anything else because it was unbearable to be alone. We sat outside a cafe and silently watched the clear white streaks high above us in the evening sky, painted by a plane with living people inside.

2.9 Kyiv, Ukraine, 2017

Wall lines

My family was happy in Kyiv. True, the five of them lived in a one-room flat, but they were happy that they had managed to rent something at least. My grandfather complained a lot that Kyiv was too Russian-speaking. However, there were Ukrainian flags everywhere and there was (so far) no war.

My grandmother could still get around a little by herself, and every day would go out for a walk along the communal corridor on their floor. She could no longer see and was quite weak, so she would lightly trace her fingers along the wall as she walked to support herself and not lose her way. In time, her palm formed a long, horizontal line rubbed into the whitewashed concrete of the wall.

This trajectory of touch, a map of a single journey, fascinated me when I saw it. I wanted to take a picture of it, but every time I came, I would forget. I will definitely do it next time, I told myself. Until the next time never came again.

2.10 Vilnius, Lithuania, 2022

Magic beans

My family found themselves in Vilnius suddenly and unexpectedly, like many other Ukrainian families who, in the spring of 2022, evacuated however and to wherever they could.

‘Going abroad for the first time in my life, imagine that!’ said my grandmother excitedly when I met them halfway in Warsaw. ‘Only, how am I supposed to live in Lithuania, when I don’t know their language?’ She was 96 years old; she could no longer see or walk on her own.

In Lithuania, to entertain my grandmother with her passion for growing vegetables, my mother bought her a bean plant in a tin can: you open the can, add a little water, the bean would sprout, and then you would have your own, real runner bean growing on the windowsill, cheering everyone up. And that’s what it did. The last time I visited them, when everyone was still together, we joked that this bean plant might grow to the very sky, like in the fairytale. After all, the can had ‘magic bean’ written on it.

My grandmother departed from us that autumn, there in Lithuania.

The runner bean never grew to the sky.

But my grandmother, I think, doesn’t need magic beans to reach it.